Contributor Essays

The AT&T Archives and History Center

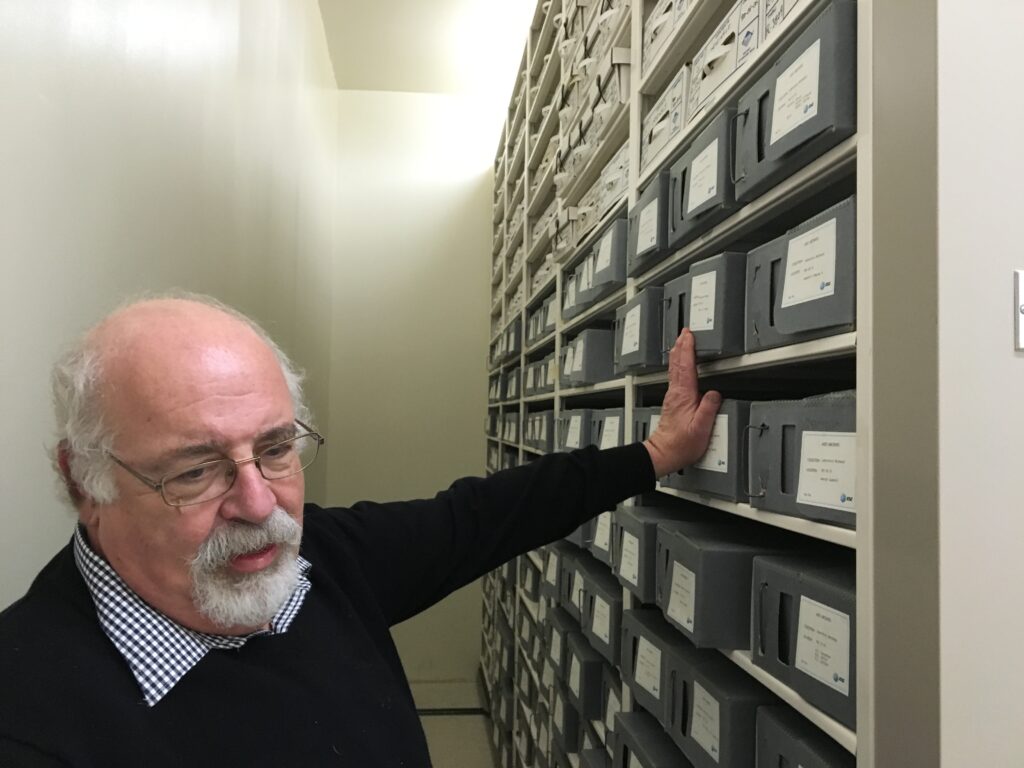

An Interview with Sheldon Hochheiser

by Xiaochang Li

April 9, 2020

The AT&T Archives and History Center contains a sprawling collection of material from the company’s corporate and research activities extending back to the origins of the American Bell Telephone Company in the 1870s. Housed within an unassuming warehouse facility in Warren, New Jersey, the collection contains roughly 35,000 cubic feet of documents, photographs, sound recordings, film and video, and microform, as well as an assortment of approximately 10,000 artifacts.

These collections form a vast repository of source material related to the history of electroacoustics in the United States, particularly in areas of speech and hearing research, telephony and telecommunications, sound engineering, signal processing, and electronics manufacturing. The archives are run by Dr. Sheldon Hochheiser, the AT&T corporate historian, who sat down with me to share his formidable knowledge regarding the center’s materials, history, and many organizational quirks. The material transcribed here is taken from that series of interview sessions on-site at the AT&T Archives and History Center on November 18–22, 2019.

The Collections

The materials housed at the AT&T Archives and History Center are assembled from five previously separate collections that originated in different parts of the company:

The Bell Labs R&D Files

SHELDON HOCHHEISER: This is one of the largest parts of the collection. All of the R&D files, going back to before it was Bell Labs. Bell Labs was created in 1925, out of the core that was the old Western Electric, our manufacturing subsidiary’s engineering department, at 463 West Street, New York. For good reason, Bell Labs were compulsive record keepers. Under American patent law, until very recently, the validity of a patent was date of invention, not date of filing paperwork, which is very different from most of the rest of the world. So, all Bell Labs scientists, all Bell Labs researchers, were issued laboratory notebooks, numbered and individually tracked. And when you filled it up, you turned it into the record keepers and you got another one, numbered and individually tracked. Now, how people used lab notebooks was very idiosyncratic. Experimentalists tend to use them because they had to write their results down somewhere. Theoreticians, some did, some didn’t. But in any case, we have approximately 100,000 laboratory notebooks from the early twentieth century through 1996. Similarly, Bell Labs had a case file system for all other paperwork associated with the R&D project. This could be memos of meetings, correspondence, drawings, and formal internal proprietary papers called Technical Memoranda. There are 100,000 volumes of those as well.

Bell Labs Non-R&D Files

SHELDON HOCHHEISER: The second piece came here once Bell Labs formed a formal archives. These were the papers other than the actual R&D papers I discussed. Supervisors, papers of senior management, advertising, collections of company publications, Bell Systems Technical Journal, The Bell Labs Record, other things [like that]. That was started in the 1970s in an administrative building and then moved here.

Bell Telephone Museum Collection

SHELDON HOCHHEISER: The third piece: there was a Bell Telephone Museum at the New York headquarters building of Bell Labs, on 463 West Street. It’s not entirely clear to me when that museum closed. It could have been as late as 1966, when we finished vacating and sold the building, that all of the contents of the museum came here, and it’s the core of the artifacts collection.

Western Electric Collection

SHELDON HOCHHEISER: The fourth piece: Western Electric was AT&T’s manufacturing subsidiary. They had an archives at their headquarters building in New York. That collection moved here in the mid-1980s, when AT&T sold that building.

AT&T Corporate Archives Collection

SHELDON HOCHHEISER: The fifth piece: so AT&T has continuously had a corporate archives since William Chauncey Langdon. This collection was formed in 1923. It reported to public relations at the time. It is very varied. There is an artifact collection there, and a photo collection. And there are records of the overall parent company going back to the very beginning. The material that came from the corporate collection basically traces the history of the parent company, of the Bell system monopoly and its nineteenth-century predecessors, going back to Alexander Graham Bell’s invention of the telephone.

The core of the corporate collection is the material Chauncey Langdon collected, and it even contains a few oral histories. Now, there’s no tape recording—he’s got a stenographer taking it down and then typing it up. There was a real attempt to collect public relations type materials and press releases, runs of company publications, photography.

Notable Materials

Early telephony papers

SHELDON HOCHHEISER: There was also a real attempt by Langdon to document the development and evolution of the telephone and the corporation. So that is another strength [of the archives]. I have a large collection of papers dealing with such early development of the telephone that’s all handwritten. So there are massive amounts of all sorts of letter books, accounting ledgers, all sorts of correspondence as they’re establishing the telephone as a commercial device. And then as it’s spreading, and very quickly. By the early 1880s there were telephone exchanges in just about every place in the country with 10,000 or more people.

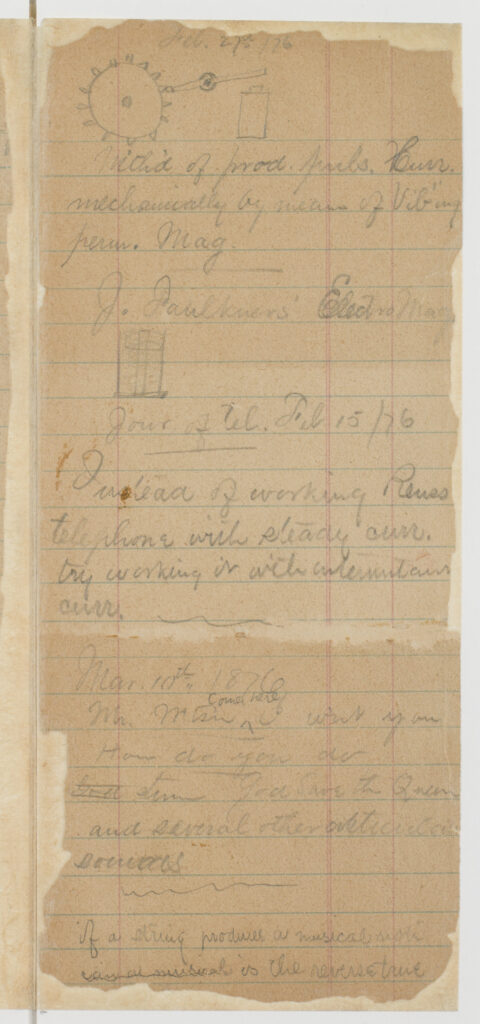

Among the greatest treasures of the archives are Thomas Watson’s notebooks from the 1870s into the early 1880s. And the most important one is the notebook that contains the entry for March 10th, 1876. That’s the day Bell first succeeded in transmitting intelligible speech. The person who heard it was Watson. Watson wrote down what he said in a standard stationery store notebook in pencil. And that’s in the vault, and that’s probably the single item in this whole massive collection that gives me the most goosebumps, even after all these years.

The photograph collection

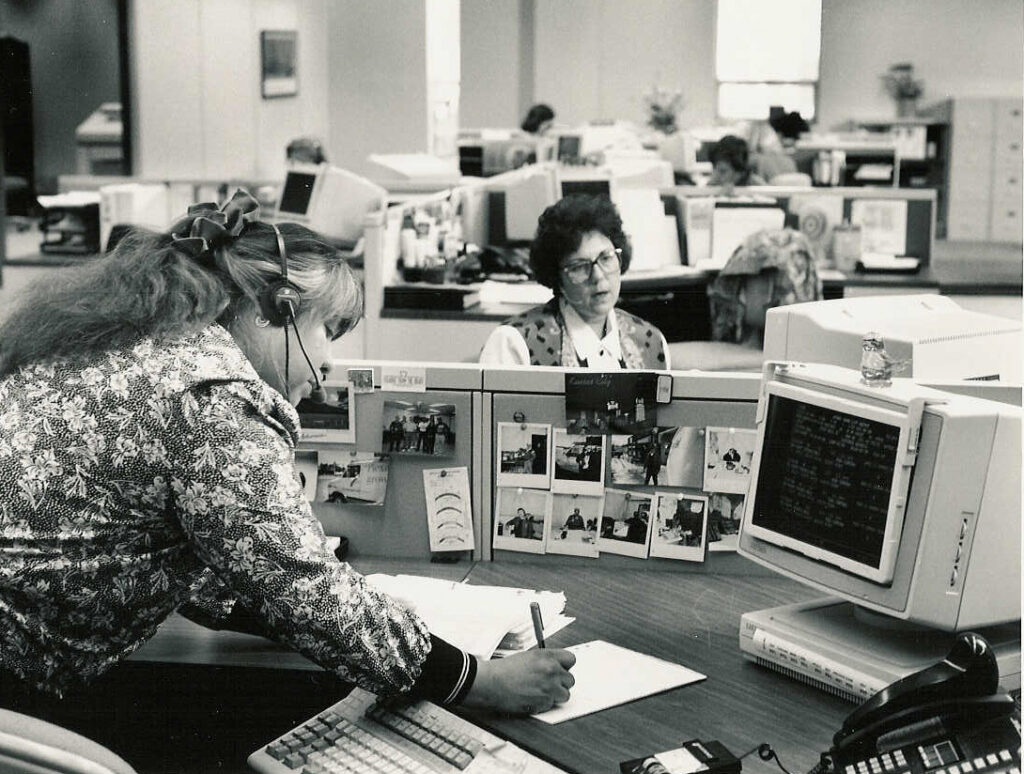

SHELDON HOCHHEISER: Another really rich collection, which cuts across all of the various components, is the photograph collection. I have over a million photographs here. The wealth of things that I can provide images for is enormous. There are certainly plenty of photos that were done for PR purposes, photos that were done for company magazines. I also have a massive collection of photos done by Bell Labs researchers in the course of doing their work. The number of photos I have of operators at work from the 1880s through the 1990s must be in the thousands.

Laboratory notebooks

SHELDON HOCHHEISER: We have 100,000 lab notebooks [from researchers at Bell Laboratories]. About 1000 of the most important ones are here [in a climate controlled bank vault]. Walter Brattain’s notebook, recording the invention of the transistor, December of 1947. John Pierce’s notebooks are in here, from when he was working on traveling wave tubes. Harold Arnold’s work, a pioneer in long distance radio transmission and the vacuum tube. Morris Tanenbaum, who invented the silicon transistor. Harold Black, who invented the negative feedback amplifier, the inventors of the solar cell. Homer Dudley, who invented speech synthesis, his notebooks are in here. George Smith’s notebooks, the invention of the CCD [charge-coupled device].

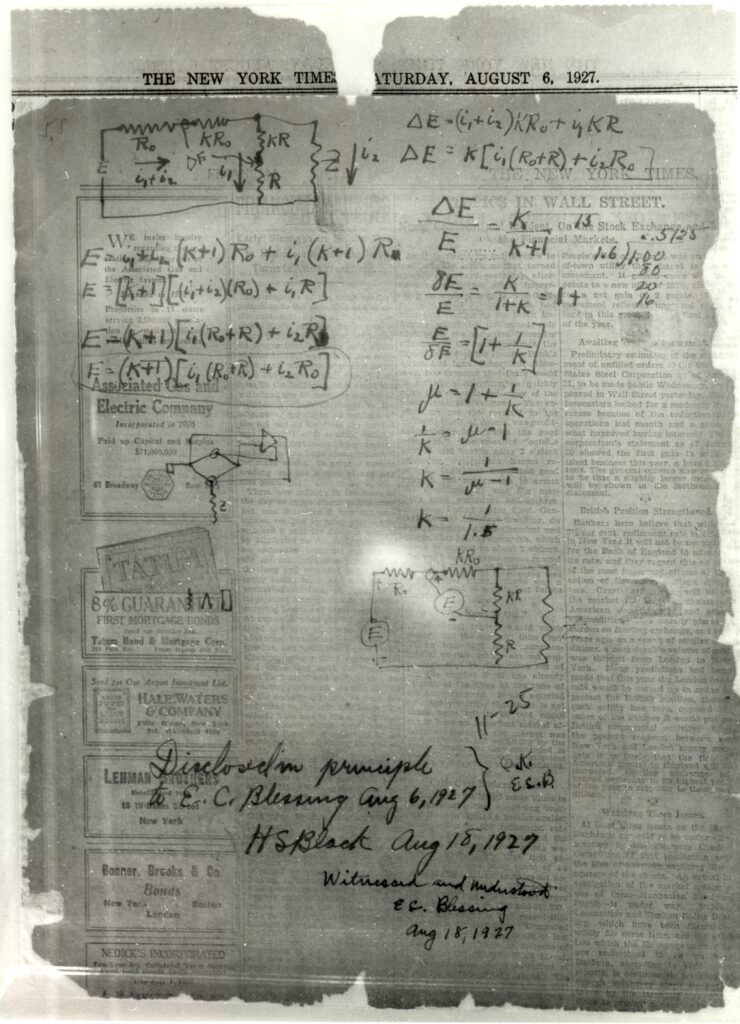

Now I mentioned Harold Black who invented the negative feedback amplifier.

The necessary equations came to him one Saturday morning while he was taking a ferry from his home in New Jersey to Bell Labs in New York. So, he was afraid that by the time he got to his lab, he’d forget the equations. He didn’t have anything to write it down on, so he bought a newspaper from a newsboy on the ferry and found a lightly printed page of the day’s New York Times and wrote the equations down. And then he got them witnessed by someone else at the labs, which was what you needed to do for legal purposes.

Sound Recording Collection

SHELDON HOCHHEISER: The audio collection contains approximately 1,800 items, ranging from experimental recordings from the 1920s and 1930s, through company presentations and programs from the 1980s and 1990s. Electrical sound recording was invented here in the 1920s. [The collection includes] our experimental metal stamping masters from Bell Labs audio research and research in sound recording and reproduction from the ’20s and ’30s. The most famous of them are of the furfrom 1931 or 1932. The Bell Labs team doing audio recording research met with Leopold Stokowski, and the result was they brought all their equipment down to the Academy Music in Philadelphia and recorded much of the 1931/’32 Philadelphia Orchestra Season. And those metal stamping masters are somewhere here. In the 1970s Bell Labs put out two LPs of the 1930s Stokowski Philadelphia Orchestra recordings. And this created quite a controversy ’cause these recordings were made in the ’30s for research purposes, that meant it turned out no releases were signed by the musicians. It turned out that Stokowski didn’t even tell the orchestra that he was doing it. So, with these recordings, the deal that they worked out was that they would not sell but give away them and then not press anymore.

Quirks of the Archive

One of the distinct challenges for external researchers at the AT&T archive is its intricate and sometimes idiosyncratic cataloguing system. Since each of the five previously separate collections in the archive came with its own cataloging system and a different set of organizing principles, the resulting arrangement for the consolidated materials became, in Hochheiser’s words, “extremely, extremely quirky.” At the center of the system is a massive database that is only accessible on-site by archive personnel.

Evolution of the database

SHELDON HOCHHEISER: Everything was cataloged in different systems. How do you deal with bringing together disparate collections that were cataloged according to different principles into one collection?

I have a massive database with three quarters of a million entries. The wizards of Bell Laboratories custom built a database for us in 1987, which was cutting edge. The other quirk is when the database came up in 1987, we were limited to one line of description. Anything entered in 1987 has a rather terse description. In 1988, they made an improvement and we could enter things in as long a format as we wanted. And dozens and dozens of people have done processing and data entry. Over the years, you try to enforce standards, but still, what you could do evolved. We certainly couldn’t attach an image to a computer record in the 1980s and early ’90s. And of course, by the early 2000s, that was easy to do. So, there’s been a lot of changes due to the evolution of technology.

Unconventional filing techniques

SHELDON HOCHHEISER: The other interesting thing is my predecessor and partners in the Bell Labs environment kept track of things using the database rather than provenance and record series or other more conventional archival techniques. So, if you were processing papers, you filled a box, and the box may have completely unrelated material. The database tells you what’s where. Similarly, our photo collection. We have a million photos and for the most part, they’re cataloged by the date they were cataloged, rather than by subjects.

The Bell Labs R&D records are exactly as they were done at the time by the clerks at Bell Labs, and this system goes back to the early 1900s. Every one of those 100,000 volumes is in our database, but the material in the database is very limited. When a case file is opened, an arbitrary number is assigned by the record keepers. These case files—and they have been variously called Case Files, Project Files, File Cases—may not necessarily be for a project, they could be for the work of a department.

One of my favorite examples of that is “mathematical research.” It’s [the case file] for all the work done by the Bell Labs Math Department that was not assigned to a specific narrow project. To the extent there were papers dealing with Claude Shannon, they’re mixed in mathematical research for the years he was there, with papers from all sorts of other members of the Math Department. All that’s listed in the database is the arbitrary number, the title, which more often than not is not terribly useful, a list of volumes, and the volumes are in reverse chronological order.

The good news is we can find stuff. For the most part, the database will bring it together. But you have to figure out what search terms you want to look for. With exceptions, you can’t just go and say, “Oh I’m looking for ads. All the ads are in this set of bookcases.” No, they’re scattered all over the place, but the database will tell me.