Contributor Essays

Variations on a Theme: The Movement of Acoustic Resonators through Multiple Contexts

by David Pantalony

July 17, 2019

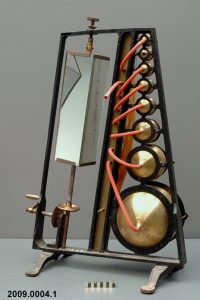

The spherical acoustic resonator was one of the foundational instruments of nineteenth-century physics, physiology, and psychology. There are still hundreds of historic examples hidden in museums and campus storage rooms in Europe, North America, Asia, and South America. They all seem to be the same thing, but upon closer examination show surprising differences in quality, wear, materials, dimensions, and local adaptations and markings. These variations reveal multiple contexts that shaped this fundamental scientific concept and instrument, but also the study of acoustics at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Transition from Glass to Brass

Hermann von Helmholtz is considered the inventor of the analytic acoustic resonator for listening to specific harmonics in compound sounds. He based this invention on Joseph Fourier’s mathematical description of periodic phenomena, as well as recent findings related to the physiology of the inner ear. Helmholtz first designed a glass resonator for inserting in the ear, and in 1859 he commissioned Rudolph Koenig to make these in Paris. Koenig used his training as a violin maker to refine and standardize Helmholtz’s design. Frustrated in his attempts to do this with glass, Koenig quickly switched to brass for ease of tuning and manufacturing. He became the most prolific maker of these brass resonators, with factory-like numbers sold around the world. However, even among Koenig’s brass resonators for the same frequency, one finds subtle differences of dimension (diameter, mouth and neck) that reveal his workshop processes of tuning and construction. He and his workers clearly paid attention to each resonator. One does not find this on the later resonators made by Max Kohl.

Koenig’s switch to brass also made the resonators more durable, reflecting a momentous shift in the market for scientific instruments. The resonators would move from Helmholtz’s controlled private laboratory space of the 1850s to the more open, decidedly less delicate, and rapidly expanding student laboratories of North America. By 1900, there were several other makers of resonators, some even faking Koenig’s stamp. Brass resonators became a visual icon for Helmholtz’s work in acoustics.

Movement between Disciplinary Contexts

Some variations in surviving resonators are due to their disciplinary context. At the University of Toronto there are two sets of nineteen resonators, in the psychology and physics departments. The resonators in the psychology collection (c. 1891) are in pristine condition with polished brass and few dents; the ones in the physics collection (c. 1878) are heavily dented with stained, worn, and corroded surfaces. These differences of wear are a common finding with Koenig instruments across many collections. For example, one finds very different histories of use with the surviving Koenig collections at MIT and the University of Coimbra. In the specific case of the resonators at Toronto, the two sets raise research questions about the distinct experimental, conceptual, and teaching cultures within which the instruments were used.

Replacing the Ear with Vibrating Flames

The most dramatic adaptation to the brass resonator came out of Koenig’s Parisian context. Whereas Helmholtz had designed the resonator to be inserted into an ear for listening directly to simple tones and harmonics, by the mid-1860s Koenig had attached a gas tube to the ear piece in order to make the vibrations “objectively” visible using manometric flames. His subsequent invention, the sound analyzer, removed the expert ear from sound analysis and made Fourier harmonics visible for research and public display. This radical change in resonator practice came into being within the highly visual traditions and context of Parisian scientific demonstration culture. Historian Gabriel Finkelstein has called nineteenth-century Paris “the Broadway of scientific performance,” with popularizing traditions that some German scientists found distasteful.

Resonators as Complex Transnational Objects

Resonators also moved across national and musical borders. The Koenig resonators in the physiology of hearing collection at the Department of Physiology, Charité, Berlin, have hand-scratched German notations beside the French notation. This was no ordinary adaptation of an instrument to local context, but one with layers of significance rooted in differences between French and German standards and notation traditions at the time.

There were certain tensions between Rudolph Koenig and the physics community in Berlin. Even though Koenig made, sold, and popularized the instruments from Helmholtz’s Sensations of Tone, by the early 1870s he and Helmholtz began to disagree about the nature of combination tones, an acoustic phenomenon that raised problematic issues between physics, sensations, and perceptions. Helmholtz approached this mystery from an analytic mathematical perspective, while Koenig, conditioned by his visual instruments and workshop practices, questioned the established Helmholtzian view. During a visit to Berlin in 1892, the American physicist Le Conte Stevens reported that a laboratory assistant warned him not to mention Koenig’s experiments in front of Kundt or Helmholtz.

Made by a German in Paris, the resonators circled back to an unwelcoming context in Berlin. Koenig was born and educated in Königsberg, but after his move to Paris in 1851 at the age of nineteen, he felt more at home in his adopted city. In the aftermath of the 1870 Franco-Prussian war, and following the disputes with Helmholtz and his colleagues in Berlin, Koenig eventually became isolated in both cultures.

Resonators within a Collection Context

The wider collection perspective provides a different context as well. There are few Koenig instruments in the Charité collection, which is similar to patterns found in other acoustical collections in Germany; it features vowel forks, and other forks from a tonometer and pitch studies. There are a variety of organ pipes with manometric flames for studying nodal properties.

However, the surviving collection at Charité does point to a robust and diverse instrument culture with several other German acoustical makers. The collection includes tuning forks by Edelmann of Munich and Zimmermann of Leipzig. There are acoustical instruments by Max Kohl, who produced many of Koenig’s instruments later in the century, and especially in the run-up to the First World War. The Tone Variators by Kohl were a popular instrument derived from the pre-Gestalt work of William Stern. Other collections in Germany (and elsewhere) have instruments made by Appunn and Sauerwald.

The resonators seemed to be an exception within German acoustical trade. The Charité resonators date from around 1882, when there were no other German makers yet producing these instruments. Berliners still depended on Koenig when studying the analysis of sound.

Katarina Preller has studied Helmholtz’s lecture notes given in the physics department at Humboldt University. Unfortunately, the instruments that formed this collection, like other collections throughout Germany, were destroyed during the Second World War. The surviving physiology of hearing collection only tells a portion of this material history.

Exploring the Materiality of Resonators beyond Acoustics

By studying these artifacts and collections, we can better understand the influence of instrument making cultures, scientific traditions, and national contexts on the history of such a fundamental acoustical and physical concept. More research needs to be done on the German makers, but it appears that German musicians and scientists benefited from a fairly diverse trade in tuning forks in particular. Investigating collections in Berlin, Dresden, Heidelberg, Leipzig, and Munich, we can build a more comprehensive inventory for comparison with other collections in France, Italy, Portugal, the Netherlands, Russia, Britain, and North America; such an inventory will allow us to study patterns of materials, manufacturing skills, and practice, and thus better understand the material dimensions of acoustics during this period. The study of these variations at the collection level could also offer insights into the history and development of resonators in general, a central class of scientific object found throughout the sciences and technology from laser resonators to quartz oscillators.