Contributor Essays

A Sound Foundation

The Early Years of the Dutch Society for Acoustics

by Karin Bijsterveld

February 26, 2018

The Dutch Society for Acoustics (Nederlands Akoestisch Genootschap) received its current name in 1962, but was established as the Sound Foundation (Geluidstichting) in 1934. Right from the start, its board aimed both to disseminate knowledge about sound and to intervene in societal issues around sound. Studying and abating noise soon became a priority. Through the Sound Foundation, Dutch scientists and engineers acquired and retained a high profile in public debates about noise. But, as I will show, they were by no means the only ones defining the problem of noise in the Netherlands.

The Sound Foundation’s first president was Adriaan Daniël Fokker, a Leiden University professor of technical physics with a deep interest in music. In the Netherlands today, Fokker is better known for building an equal-tempered thirty-one-tone organ than for his Sound Foundation work, but he was instrumental in getting the Foundation off the ground. One of his fellow physicists, professor Cornelis Zwikker, was involved in the acoustical testing and inspection of materials at the Delft Laboratory for Technical Physics. Together, Fokker and Zwikker wanted to make this work more official, authoritative, and centralized, for instance by unifying acoustical nomenclature. They raised the issue with the Foundation for Materials Research (Stichting voor Materiaal Onderzoek), which had a commit tee studying acoustical characteristics of building materials—Zwikker was a member. The physicists and the engineers joined forces to establish a foundation that would focus on sound in the widest sense of the word: sound within the auditory range, infra- and ultrasound.

Society, these experts claimed, was struggling with many issues related to sound, such as the sound insulation of high-rise buildings, city noise, and the acoustics of concert halls and radio studios. It was thus in dire need of scientific research that could lead to suggestions for maximum permitted sound levels or for actual noise abatement. The Sound Foundation’s official purposes included the design of guidelines for home-building and the inspection and measuring of construction materials . This emphasis on professional practice may well have partially stemmed from worries about the insecure job market at the time, but the Foundation also aimed to provide noncommercial advice and public education.

It was not immediately clear what exactly those public education efforts should address. Initially, the Sound Foundation hesitated over which topic was most appropriate for a public campaign. It certainly had to be a tangible one in order to attract public attention. By chance, the Sound Foundation discovered that the Royal Dutch Automobile Club (Koninklijke Nederlandsche Automobiel Club) was planning to orchestrate “silence weeks,” where traffic participants would be educated into conduct likely to reduce street noise. For the Automobile Club, the silence weeks also offered an opportunity to promote the automobile in general, since the orderly behavior of all traffic participants literally cleared the way for the car; for the new Sound Foundation, cooperation with the Automobile Club offered a source of financial backing. Such considerations fed into the choice of traffic noise for the campaign.

In both 1934 and 1936, the Sound Foundation organized Anti-Noise Conferences in cooperation with the Automobile Club. Fokker believed such conferences might contribute to a more civilized culture. To fight the “demon” of noise, he argued, one had to set out “the ideal of the expert professional who silently knew how to control his noiseless machine” against the “noise vulgarian” and “motor yokel” who tried to impress others by making noise (Publications Geluidstichting No. 1: 16). The despised sounding of car horns, most contributors made clear, had to be eliminated first (fig. 1).

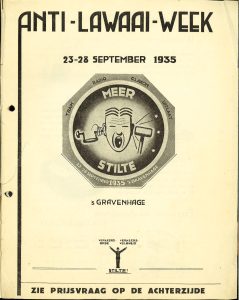

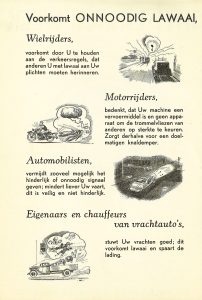

Accordingly, in 1935 and 1936, local noise abatement committees organized silence campaigns in Breda, The Hague, Rotterdam, Groningen, and the province of Limburg, often in cooperation with the police and motorist organizations. During “silence weeks,” “silence months,” and “silence exhibitions,” campaigners distributed thousands of pamphlets (fig. 2). Dozens of newspaper articles, radio broadcasts, and cinema news reels covered the campaigns. The basic principle was to familiarize civilians with the idea that they must look before sounding their horns: “Use your eyes instead of your horn,” one pamphlet advised. Similarly, pedestrians and cyclists should learn to behave correctly: pedestrians must cross intersections in a straight line, cyclists should stay on the right side of the road. In sum, people should watch out, stay right, and slow down. In addition, they should fit exhaust mufflers and refrain from using their motor to test other people’s eardrums (fig. 3). The back page of one pamphlet even advertised a competition with questions on proper traffic behavior, won by a musician who stressed that all traffic participants could contribute to decreasing the din of car horns (see also).

One of the campaign’s slogans, “Orderly Traffic Promotes Silence” (fig. 4), typifies the unlikely discourse coalition between motorists and anti-noise activists. The slogan’s dual meaning evoked both less congested streets—the interest of the automobile owners—and a reduction of the fatiguing chaos of sounds, reflecting the activists’ aims. It merged two different, if not opposing, definitions of the street noise problem into one approach to noise.

The Dutch silence campaigns succeeded in diminishing the use of car horns, at least locally and temporarily. Because the campaigns were so car-friendly, however, they did not help to reduce noise more generally—on the contrary. Much remained to be done by the Sound Foundation. In 1937, it launched a separate Anti-Noise League so that it could focus more fully on research (see also 1). The Sound Foundation’s research publications reported on noise abatement, noise control, sound insulation, and hearing problems, but also on sound level measurement, architectural acoustics, air alarm sirens, stereophony, magnetic recording, ultrasound, and—Fokker’s legacy—microtones. The Dutch Society for Acoustics received its current name in 1962. But the Sound Foundation had served as its sound foundation.

Note from the editors: The NAG archives are currently stored at the offices of M+P Consultants, in Vught, The Netherlands. Access a selection of these archives in our database here.