Contributor Essays

Mimicking the Voices of Nature

The Sounds of Hunting in Twentieth-Century America

by Alexandra Hui

June 12, 2018

Early European settlers brought firearm technology to waterfowl hunting in the Americas. In the late eighteenth century, market hunting of the goose and duck flocks of the Atlantic and Mississippi Flyways proliferated. Hundreds of bird species move along the Atlantic coast and from the headwaters of the Mississippi River in Minnesota and Ohio to the Gulf of Mexico, migrating between breeding grounds and wintering grounds, and in the nineteenth century, hunters began using sound to draw down these passing birds.

The earliest documented duck call instrument dates to 1854, a tongue pincher design. The first US patent for a duck call was issued in 1870. Printed material advertising hand-turned duck calls can be found as early as 1880. Several of the call designs were established in this period, among them the P.S. Olt D-2 adjustable tone duck call, a reed design claimed to be the most popular duck call of all time. Wetlands restoration and innovations in mass-production of duck calls fueled and were facilitated by an explosion in duck call production in the 1930s. In addition to the traditional materials of wood and cane, these new factory-made calls were fashioned from plastic and hard rubber. Reeds were made of metals such as copper, brass, and tin as well as rubber, plastic, and cane.

Duck call sounds have a historical and regional variability that indicates both the changing preferences of the hunters and the birds’ changing behavior as they move down the Flyways. The temporal and regional variation in the sounds of waterfowl mimicry can be traced in the ephemera—both material and auditory—of modern hunting. As duck call production exploded in the 1930s, so too did marketing and training materials. These materials reflect an effort to expand and standardize the sounds of hunting. They also offer hints about how hunters conceived of the role of sound in their relationships to their quarry.

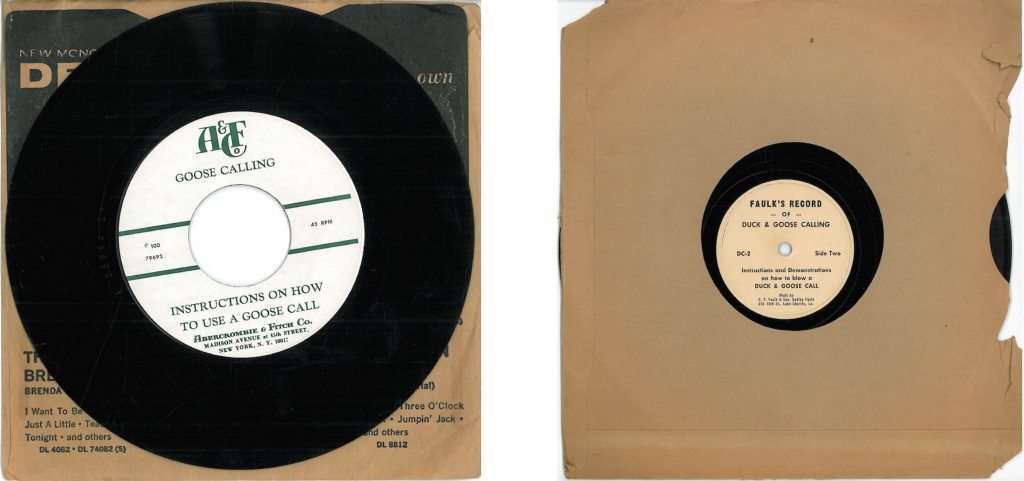

At the same time that bird sounds recorded in the wild were being released and promoted to aid in ear-training professional and avocational ornithologists, champion callers and call manufacturers were producing call-training records. These were not recordings of animal sounds but rather of the human mimicry of animal sounds. They were created for novices, explaining how to hold the call with the hand, how to move the air from one’s diaphragm through the call, and so on. One did not simply say “quack” into a duck call. Only specific sounds blown into the call could be transformed by the call into credible duck sounds. The training records encouraged callers to practice these sounds slowly and steadily, gradually increasing speed and volume. In this way, we can observe the duck-calling community’s understanding that the mastery of a duck call, requiring the cultivation of physical and improvisatory skills, was very much like mastering a musical instrument.

But hunters also needed to master the role of sound in animal behavior. Different types of calls were necessary to get the attention of the passing birds, bring them down, or encourage them to turn around. The Highball Call, for example, was a series of three loud, high quacks and then three more that descended in pitch and volume, whereas the Feed Call slid up in pitch on the first note—“qua-QUACK”—then immediately descended over five quacks to a mumbly “dugawdugawdugaw.” The caller was encouraged to practice the various calls and learn to read the birds’ movements in order to use the appropriate one. To that end, both records and printed material provided sample hunting scenarios—little scripts and chord sheets, if you will.

In the early 1960s, Wightman Electronics developed a portable record player rugged enough to be used in the duck blind. The “Call of the Wild” device ran on batteries, and included a loudspeaker and a set of recordings of ducks and geese made in the wild. It was so effective at drawing down birds—the animals believed the recorded sounds were their compatriots—that it was immediately banned by federal law for use in waterfowling. However, until the introduction of cassette tapes and now phone apps, it remained popular (and legal) for the hunting of pest species.

The use of recorded sound in hunting is part of the larger trend of recording sounds of nature. Playing these records back for the recorded species, thus taking advantage of the animals’ sociability in order to hunt them, adds a cruel twist. In the heyday of bird call recordings, anecdote suggested that crows, especially, grew more suspicious of each other, of their own voices. We might contrast the use of recorded nature sounds in nature with the simultaneous proliferation of recorded nature sounds in built, human spaces in the 1960s, or perhaps the behavior of the listener is being manipulated in both cases.

We can think of the mimicry of nature sounds as an epistemological practice. We might ask what the criteria was for establishing the quality of mimicry—and what species were the judges? The training manuals and records, the marketing ephemera, and the duck calls themselves all offer insights into how hunters listened. The practice of mimicry can tell us something about how nature was understood, and maybe even about what nature sounded like in the past.