Contributor Essays

Sound Archiving and Discipline Formation in Berlin around 1900

by Viktoria Tkaczyk

April 6, 2018

Sound is ephemeral. For a long time, it escaped scientific scrutiny, and the invention of the phonograph in the 1870s was celebrated as a long-awaited research tool in both the humanities and the sciences. Before long, various scientific sound archives had been founded for the systematic collection, preservation, and study of sound recordings. Two of these early archival endeavors were located in Berlin: the Phonogramm-Archiv (“phonogram archive”), today part of the Ethnological Museum’s department of ethnomusicology, and the Lautarchiv (“sound archive”), now based at the Humboldt University, Berlin.

The Phonogramm-Archiv was initiated in 1900 by psychologist Carl Stumpf and his assistant Erich Moritz von Hornbostel. What started as a private collection, based at Stumpf’s Institute of Psychology in Berlin, soon grew into an immense enterprise that was transferred to the Academy of Music in 1923, with parts moved to the Museum für Völkerkunde in 1934. During this early period, a valuable collection of roughly 30,000 Edison cylinder recordings came together through Stumpf’s vast personal network of traveling colleagues, friends, and acquaintances. These recordings have been celebrated as the foundation stone of an emerging disciplinary field, the “Berlin school of comparative musicology,” and in 1999 the collection was added to the UNESCO Memory of the World Register. Many of the field recordings staked preservationist, if not colonial, claims, aiming to collect and research all the world’s languages, musics, and sounds.

In parallel, Stumpf and his colleagues found ways to turn the phonograph into a research tool for tone psychology, as documented by a smaller collection of roughly a hundred Experimentalwalzen (experimental cylinders).

Some of these recordings derive from experiments with vowels, whispers, and intelligible speech that Stumpf conducted for his 1926 book Die Sprachlaute (The Sounds of Language). For this study, Stumpf also produced an intriguing set of laboratory notebooks that document his interest in technologies of sound analysis and synthesis. Another series of experimental recordings is discussed in Otto Abraham’s 1922 study “Tonometrische Untersuchungen an einem deutschen Volkslied” (Tonometric Studies with a German Folksong), which was intended to provide comparative data for studies on non-European song. To test and compare his European subjects’ absolute pitch in producing sung intervals, Abraham asked twelve colleagues to sing or whistle the well-known melody “Song of the Germans” (Haydn, with lyrics by von Fallersleben) by heart. He found that even the singing of well-trained test subjects with absolute pitch deviated from theoretically defined intervals; in some cases it exceeded all the differences between just intonation and equal temperament. The recordings led Abraham—much to his own surprise—to abandon his earlier claim that “absolute tone consciousness” could be deduced as successfully from test subjects’ tone judgments as from their singing or whistling (Das absolute Tonbewußtsein, 1–2, 5–6, 73). Abraham also carried out a series of phonographic studies on the musicality of children and animals, none of which is preserved today.

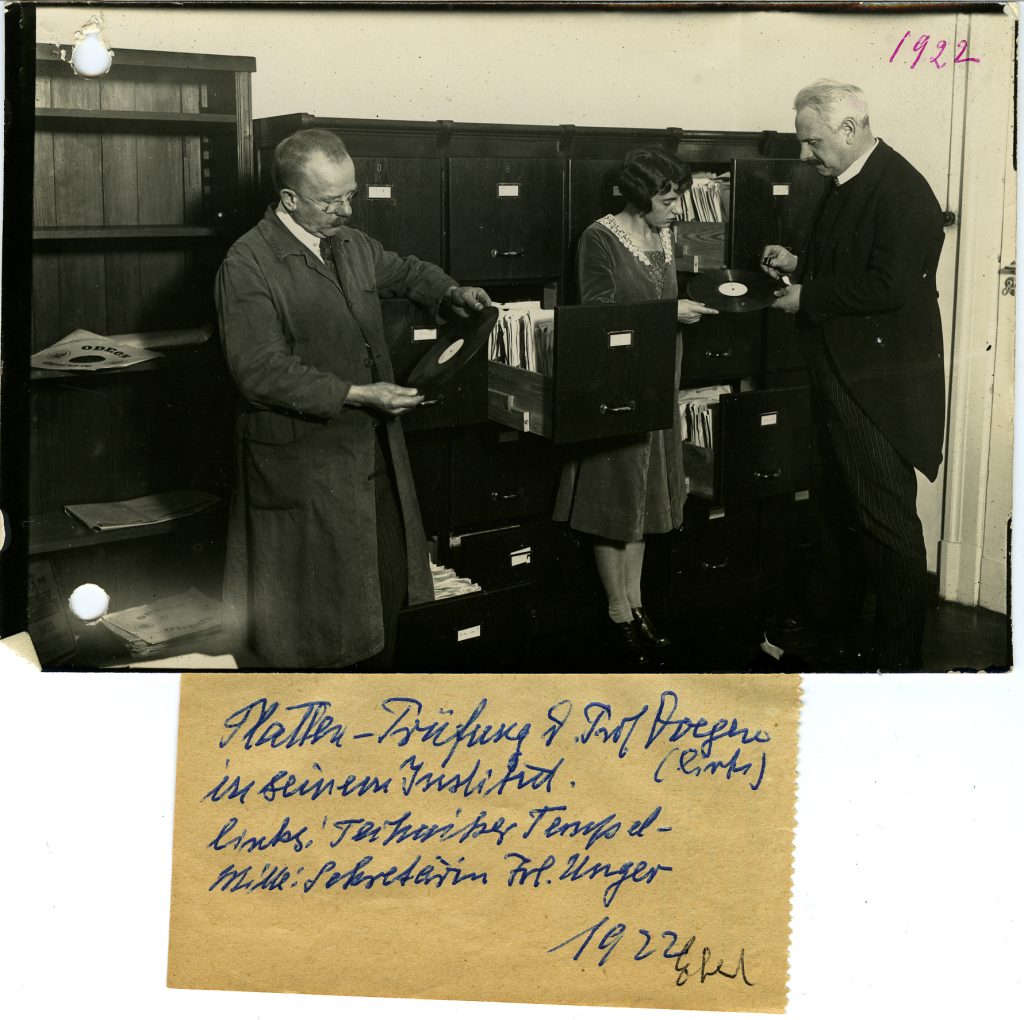

The Phonogramm-Archiv’s experimental cylinders facilitated the rise of a range of new scientific disciplines, from comparative musicology, to tone psychology, to music pedagogy and ornithology. The same is true of another, slightly younger Berlin sound archive, the Lautarchiv, initiated by Stumpf and the language teacher and phonetician Wilhelm Doegen. In 1915, Stumpf and Doegen founded the Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission to record and archive the languages and music of “colonial” prisoners of war interned near Berlin—not without claiming German interpretive sovereignty over their sound cultures.

After the war, Stumpf continued his research in the framework of the Phonogramm-Archiv in Berlin, while Doegen, formerly managing director of the Phonographic Commission, moved to help found the Lautabteilung (“sound department”) of the Prussian State Library in 1920. Ten years later, in 1931, the Library’s Lautabteilung was taken over by the University of Berlin. During World War II, the postwar years, and the GDR period it was affiliated with various different university departments and research interests, changing its name many times (a chronology can be found here). Today, as the Lautarchiv, it contains 7,500 shellac recordings, and smaller collections of wax cylinders, tapes, and aluminum discs that document a wide variety of languages and dialects along with “voice portraits” of famous public figures of the German Reich and the Weimar Republic. Because these recordings were mostly produced without the subjects’ knowledge or consent, they are not accessible online.

Regarding scientific discipline formation, the Lautabteilung’s organizational chart for 1929 reveals a complex infrastructure in interwar Germany. One of its many aims was to foster research in physical acoustics and experimental phonetics and to refine sound technologies. Doegen collaborated with the Odeon company in Berlin to improve the “glyphic” gramophone recording technique (lateral recording—“Berliner Schrift”—using a cut sapphire or ruby), hoping to deploy the technique for spoken-word recording and especially for the “faithful reproduction of unvoiced and voiced consonants” (“Die Lautabteilung,” 256). In 1924, Doegen patented the Lauthalter, or “sound-holder,” a mechanical tool that enabled repeated playback and analysis of short sequences of a gramophone recording. Doegen’s continued interest in the temporal structures of speech (or rather, of phonemes) also becomes apparent in his autobiography (36–39), where he reports on the use of an electric oscilloscope to analyze frequencies, amplitudes, rise times, and time intervals of the German impersonal pronoun man, as extracted from a recording of Germany’s last emperor, Wilhelm II, and documented in an annotated oscillogram of 1927.

Doegen’s broader aim, however, was to establish an archiving institution that exceeded experimental phonetics—fostering cross-disciplinary research with the help of leading experts in disciplines ranging from phonetics, linguistics, language studies, and dialectology to musicology and theater studies, ethnology, anthropology, cultural studies, zoology, criminology, medicine, and psychology.

In view of this multifaceted agenda, Doegen thought his Lautabteilung could also help to legitimize and institutionalize new fields of applied research. In this role, the Lautabteilung supported the political agenda of the state authorities to which it was officially affiliated in the 1920s: Doegen’s department stood squarely in the service of institutions, such as the Prussian Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, committed to promoting German language and culture.

Three sets of gramophone recordings exemplify this application orientation in the Lautabteilung’s research. The first is a series of recordings produced in 1925 by Doegen and the Greifswald linguist Theodor Siebs to promote Siebs’s book Die Deutsche Bühnenaussprache (German Stage Pronunciation), first published in 1898 and reprinted numerous times throughout the twentieth century.

The second is a set of recordings for “psychotechnical aptitude selection,” produced in 1926 by Doegen and the Stuttgart psychologist Fritz Giese. Finally, Doegen also proposed to use sound recording as a testing device in forensic psychology. Working with the dialectologist and criminologist Erhard Riemann, he set up a large-scale project to analyze the physiognomy of criminals’ voices. (Doegen reported on his research on the criminological recordings in the lecture “Stimmportraits im Dienste der Deutschen Polizei,” Voice Portraits in the Service of the Berlin Police, as announced in Verwaltungsakademie Berlin, Vierte Preußische Polizeiwoche, but neither his nor Riemann’s work has survived.) For example, the Lautarchiv holds recordings of Erwin Bohm, who had escaped from the lunatic asylum of the Charité hospital in Berlin and was then detained in Moabit prison. In 1926, Bohm was asked to recount his experiences at the asylum and read the “Wenker’sche Sätze,” a set of sentences designed by linguist Georg Wenker in the 1870s to compare the German dialects.

The experimental cylinders of the Phonogramm-Archiv and the three sets of Lautarchiv recordings that I have described differ fundamentally from the majority of the archival items held in similar institutions. Most such holdings were regarded by their collectors as backward-looking, as recordings that document facts, norms, and rules and preserve them for succeeding generations. The recordings presented in this essay, by contrast, followed a “counter-archival” impetus. They provided materials for experiments, tests, and training—future-oriented phenomena that aim to sound out cultural techniques and to apply, implement, and standardize new norms.

By Viktoria Tkaczyk

For a more detailed discussion of the Lautarchiv in the Weimar period, see:

Tkaczyk, Viktoria. “Archival Traces of Applied Research: Language Planning and Psychotechnics in Interwar Germany.” Technology and Culture, vol. 60 no. 2, 2019, pp. S64-S95.